A wise friend of mine once said

that marriage is not about standing face-to-face

gazing into each other’s eyes,

but rather is about standing side-by-side,

facing the world together.

This idea runs somewhat counter

to popular, romantic notions of marriage

that focus exclusively on the love of the spouses for each other.

Don’t get me wrong; this love is important;

C___ and G___ would not be here today

if they did not love each other.

But marriage does not simply link two people together.

Rather it places the couple

within a much wider network of relationships

that can be extremely complicated.

When you marry, you are marrying not just your spouse,

but also his or her family, friends, colleagues,

sports teams, favorite musicians, and even ethnicity.

Indeed, one of the challenges of marriage

is learning to negotiate that complexity.

But it is also part of the richness:

when I got married, I acquired not only a wife,

and eventually children,

but what was to my mind

an extraordinarily large Irish Catholic family,

a set of expectations about how and where

holidays should be celebrated,

and a professional football team I was expected to root for.

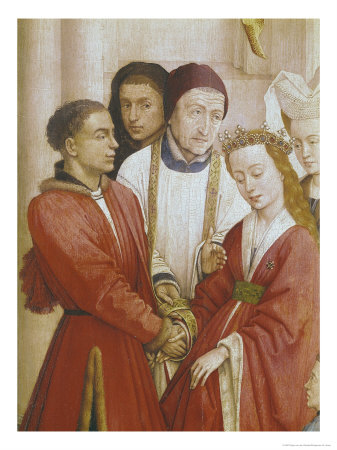

This has always been the nature of marriage,

as we can see in our first reading,

which tells the first part of the story of Ruth

from the Old Testament.

She is a foreigner, a Gentile,

who marries into a Jewish family

and as a part of all this

becomes a worshiper of the God of Israel.

When her husband, her original link to that family, dies,

she is offered by her mother in law, Naomi,

the chance to cut her ties to them

and go her own way,

back to her own people

and her own gods.

In what to our ears

sounds like something one might speak to a spouse,

Ruth tells Naomi, “Wherever you go I will go;

wherever you lodge I will lodge.

Your people shall be my people

and your God, my God.

Where you die I will die,

and there be buried.”

For Ruth, her marriage had placed her

within a web of relationships, traditions and beliefs

that permanently altered who she was as a person.

Marriage calls us not simply to be faithful to our spouse,

but into a wider faithfulness,

a faithfulness to family, friends, sports teams,

and even to God.

This is why in the Catholic tradition

we call marriage a sacrament:

it is a sign that points beyond itself

to an ultimate reality –

the reality of God’s love.

It points to the reality that,

as St. Paul said in our second reading,

“we, though many, are one body in Christ

and individually parts of one another.”

But in order to be a true sign,

it is not enough for C___ and G___

to love one another,

or even to love

each other’s family and friends and sports teams,

but they must love in a particular way.

What St. Paul writes to the Romans

is a pretty good description

of the love that married couples

ought to have for each other:

“Let love be sincere. . . .

love one another with mutual affection;

anticipate one another in showing honor. . . .

Rejoice in hope,

endure in affliction,

persevere in prayer. . . .

Rejoice with those who rejoice,

weep with those who weep. . . .

If possible, on your part, live at peace with all.”

In John’s Gospel, Jesus puts it even more succinctly:

“love one another as I have loved you.

No one has greater love than this,

to lay down one’s life for one’s friends.”

C___ and G___,

that is what you are doing here today:

laying down your lives for each other,

entrusting your lives to each other,

saying, “wherever you go, I will go.”

Your lives now belong to each other,

and in belonging to each other

you belong to the whole world.

In loving each other sincerely and faithfully,

you will be a sign to the world

that true happiness is found

not in power

or in prestige

or in possessions,

but in the kind of love

that will lay itself down for another,

in the love that seeks

to live in peace with all.

What you do here today is, I know,

important to you.

It is important to your families.

it is important to your friend.

But even more than that,

it is important to the world:

a world that desperately needs a sign

that love can overcome hate,

that generosity is more powerful than greed,

that peace can prevail over violence.

You can be that sign.

In what you do together here today,

in what you do tomorrow,

in what you do for the rest of your lives,

you become,

in what will often be small

and undramatic ways,

a sign from God,

a sign of hope.

As Jesus said to his disciples, I say now to you:

“Go and bear fruit that will remain.”

May God bless you.