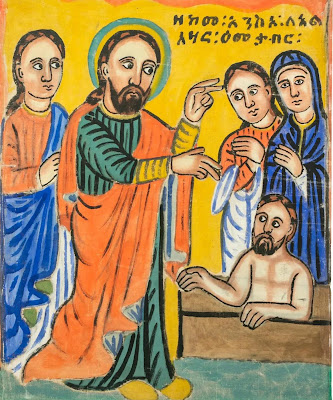

Readings: Ez 37:12-14; Rm 8:8-11; Jn 11:1-45

“Jesus wept.”

Lazarus has died,

but it is not the thought

of Lazarus in the tomb

that wakens weeping in Jesus;

it is the sight of Mary mourning,

grief-stricken at the death of her brother.

He weeps not for Lazarus,

for Jesus is the resurrection and the life

and knows that he will soon

call forth Lazarus from the tomb.

He weeps with Mary and the others

so that he may meet them in their mourning.

Lazarus has died,

but it is not the thought

of Lazarus in the tomb

that wakens weeping in Jesus;

it is the sight of Mary mourning,

grief-stricken at the death of her brother.

He weeps not for Lazarus,

for Jesus is the resurrection and the life

and knows that he will soon

call forth Lazarus from the tomb.

He weeps with Mary and the others

so that he may meet them in their mourning.

Jesus wept.

He weeps because he is truly human—

like us in all things but sin—

and the truly human thing

to do in the face of death

is to weep together.

The God who in the beginning

gathers the waters into oceans,

who in the waters of the Great Flood,

cleanses the earth,

who at the Red Sea parts the waters

to save his people,

who in the wilderness

brings forth water from the rock,

now draws tears from his human eyes

so to be like us in all things but sin—

not feigning sorrow,

not play-acting humanity,

but knowing what only a human being can know:

the experience of human grief from the inside.

He weeps because he is truly human—

like us in all things but sin—

and the truly human thing

to do in the face of death

is to weep together.

The God who in the beginning

gathers the waters into oceans,

who in the waters of the Great Flood,

cleanses the earth,

who at the Red Sea parts the waters

to save his people,

who in the wilderness

brings forth water from the rock,

now draws tears from his human eyes

so to be like us in all things but sin—

not feigning sorrow,

not play-acting humanity,

but knowing what only a human being can know:

the experience of human grief from the inside.

Jesus wept.

He is “perturbed and deeply troubled,”

because, though sinless,

he still bears the weight of sin,

and the weight of sin is sorrow.

He mourns at the tomb of Lazarus—

not as those who mourn without hope,

for he is himself the world’s hope,

the resurrection and the life—

but still he mourns.

He mourns the sheer fact of death,

“the veil that veils all peoples,

the web that is woven over all nations,”

the sign of our exile from the God of life.

He mourns the decay of the flesh

that God once formed from the dust

and breathed his own Spirit into.

He mourns to see God’s work undone.

He is “perturbed and deeply troubled,”

because, though sinless,

he still bears the weight of sin,

and the weight of sin is sorrow.

He mourns at the tomb of Lazarus—

not as those who mourn without hope,

for he is himself the world’s hope,

the resurrection and the life—

but still he mourns.

He mourns the sheer fact of death,

“the veil that veils all peoples,

the web that is woven over all nations,”

the sign of our exile from the God of life.

He mourns the decay of the flesh

that God once formed from the dust

and breathed his own Spirit into.

He mourns to see God’s work undone.

Jesus wept.

He weeps because he does not want us

to weep hopelessly without him.

Jesus stands outside the tomb of Lazarus,

but he knows the day is close at hand

when he will enter into his own tomb

so that the place of death

might become the place of life.

He wants to dwell in us in our weeping,

to breathe his Spirit in us once again,

to give life to our mortal bodies.

And he wants us to dwell in him,

to be knit together as members of his body,

so that just as he knows our weeping,

we in turn may know his joy.

He weeps because he does not want us

to weep hopelessly without him.

Jesus stands outside the tomb of Lazarus,

but he knows the day is close at hand

when he will enter into his own tomb

so that the place of death

might become the place of life.

He wants to dwell in us in our weeping,

to breathe his Spirit in us once again,

to give life to our mortal bodies.

And he wants us to dwell in him,

to be knit together as members of his body,

so that just as he knows our weeping,

we in turn may know his joy.

Jesus wept.

And in weeping he teaches us

that while we are still journeying in this life

pain and sorrow and hardship remain,

even for those who have been reborn in Christ.

Indeed, for those of us who seek to follow Jesus,

in some sense our sorrow must grow greater,

for we are called to imitate our Master

in making our own the suffering of the world.

The hunger of the poor,

the pain of the sick,

the fear of those afflicted by war,

the grief of those in mourning,

the uncertainty of the displaced,

the cravings of the addict,

the despair of the faithless,

innocent suffering,

guilty suffering,

all of this must touch our heart,

all of this is given us to bear

together as members of Christ’s body.

And in weeping he teaches us

that while we are still journeying in this life

pain and sorrow and hardship remain,

even for those who have been reborn in Christ.

Indeed, for those of us who seek to follow Jesus,

in some sense our sorrow must grow greater,

for we are called to imitate our Master

in making our own the suffering of the world.

The hunger of the poor,

the pain of the sick,

the fear of those afflicted by war,

the grief of those in mourning,

the uncertainty of the displaced,

the cravings of the addict,

the despair of the faithless,

innocent suffering,

guilty suffering,

all of this must touch our heart,

all of this is given us to bear

together as members of Christ’s body.

Our catechumens, who will be baptized at Easter,

come asking to become members of Christ’s body,

not so that they may leave all weeping behind,

as if being a follower of Jesus

could magically remove the weight of mortal flesh.

They come so that they may weep within him,

so that they may mourn the world’s pain,

not as those without hope,

but as those who have died through baptism

and have found in those waters

Christ who is resurrection and life.

come asking to become members of Christ’s body,

not so that they may leave all weeping behind,

as if being a follower of Jesus

could magically remove the weight of mortal flesh.

They come so that they may weep within him,

so that they may mourn the world’s pain,

not as those without hope,

but as those who have died through baptism

and have found in those waters

Christ who is resurrection and life.

This day we are bidden to pray

for those who will soon be baptized.

We pray for them because the struggle

to strip off your old self

and clothe yourself in Christ

is something none of us can do alone.

And we must pray for ourselves as well,

for we too are engaged in the daily battle

to live for Christ and not for ourselves,

to let his life grow within us

so that we, in some small way,

bring that life into our world’s

for those who will soon be baptized.

We pray for them because the struggle

to strip off your old self

and clothe yourself in Christ

is something none of us can do alone.

And we must pray for ourselves as well,

for we too are engaged in the daily battle

to live for Christ and not for ourselves,

to let his life grow within us

so that we, in some small way,

bring that life into our world’s

places of death.

As we draw close to the Easter feast,

the feast of resurrection and life,

let us ask for the grace to mourn,

so that God in his mercy

might have mercy on us all.

As we draw close to the Easter feast,

the feast of resurrection and life,

let us ask for the grace to mourn,

so that God in his mercy

might have mercy on us all.