The season of Lent is offered to us

as a time of self-examination.

But why would we need to examine ourselves?

Normally when we speak of examining things

we are trying to find out something that is

somehow obscure or hidden from us.

Doctors examine patients

to see if there might not be ailments

that are not immediately apparent.

Teachers subject their students to examinations

to find out what knowledge they have

hidden away in their heads.

Juries are invited to examine evidence

to uncover the truth of what has occurred.

So why should we need to examine ourselves?

Can I be obscure to myself,

hidden from myself?

as a time of self-examination.

But why would we need to examine ourselves?

Normally when we speak of examining things

we are trying to find out something that is

somehow obscure or hidden from us.

Doctors examine patients

to see if there might not be ailments

that are not immediately apparent.

Teachers subject their students to examinations

to find out what knowledge they have

hidden away in their heads.

Juries are invited to examine evidence

to uncover the truth of what has occurred.

So why should we need to examine ourselves?

Can I be obscure to myself,

hidden from myself?

The fact that the Church calls us

to self-examination during the season of Lent

suggests that this may actually be the case.

It suggests that we may have a way of hiding from ourselves,

deceiving ourselves about the state of our own souls,

convincing ourselves to ignore certain truths about who we are.

Jesus himself suggests as much in today’s Gospel,

saying that if we find ourselves thinking

that those who suffer tragic misfortune

must have been great sinners,

and a lack of tragic misfortune in our lives

must be a sign of our virtue,

we are fooling ourselves.

Jesus breaks through such self-deception,

saying, “I tell you, if you do not repent,

you will all perish as they did!”

Paul makes a similar point

in his letter to the Corinthians.

After he recounts the unfaithfulness

of the Israelites in the desert after the Exodus,

he warns his readers not to grow too smug

about their standing before God;

the unfaithfulness of their ancestors in faith

should rather stand as a warning to them:

“whoever thinks he is standing secure

should take care not to fall.”

to self-examination during the season of Lent

suggests that this may actually be the case.

It suggests that we may have a way of hiding from ourselves,

deceiving ourselves about the state of our own souls,

convincing ourselves to ignore certain truths about who we are.

Jesus himself suggests as much in today’s Gospel,

saying that if we find ourselves thinking

that those who suffer tragic misfortune

must have been great sinners,

and a lack of tragic misfortune in our lives

must be a sign of our virtue,

we are fooling ourselves.

Jesus breaks through such self-deception,

saying, “I tell you, if you do not repent,

you will all perish as they did!”

Paul makes a similar point

in his letter to the Corinthians.

After he recounts the unfaithfulness

of the Israelites in the desert after the Exodus,

he warns his readers not to grow too smug

about their standing before God;

the unfaithfulness of their ancestors in faith

should rather stand as a warning to them:

“whoever thinks he is standing secure

should take care not to fall.”

We human beings, it seems,

have a propensity for self-deception.

Saint Catherine of Siena said that this is why

we must make self-knowledge

the foundation of our spiritual lives;

we must dwell, as she put it,

in the house of self-knowledge.

But how do enter into

this house of self-knowledge?

How do we examine ourselves

so as to overcome

our propensity to self-deceive?

Is self-examination simply a matter

of cataloging our sins and failings,

of minutely poring over all

that we have done wrong?

I don’t think so,

for we are not only more miserable

than we will admit to ourselves,

we are also far greater

than we are willing to recognize.

have a propensity for self-deception.

Saint Catherine of Siena said that this is why

we must make self-knowledge

the foundation of our spiritual lives;

we must dwell, as she put it,

in the house of self-knowledge.

But how do enter into

this house of self-knowledge?

How do we examine ourselves

so as to overcome

our propensity to self-deceive?

Is self-examination simply a matter

of cataloging our sins and failings,

of minutely poring over all

that we have done wrong?

I don’t think so,

for we are not only more miserable

than we will admit to ourselves,

we are also far greater

than we are willing to recognize.

Saint Catherine says that we

cannot come truly to know ourselves

without knowing God.

And what we must know

about ourselves and about God

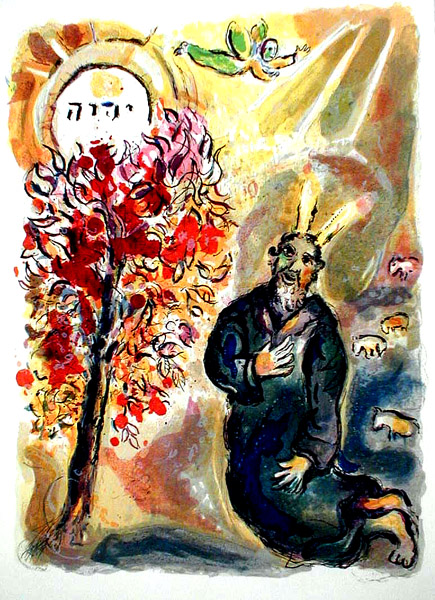

is that God is, as he declares to Moses,

“I am who am”—the One who is—

and we, in contrast, are the ones who are not.

What Catherine means by this

is that it is God’s very nature to exist,

and that everything else in the universe

has been created by God from nothing.

So while God is the One who is,

we are beings who have been drawn by God

out of nothingness into existence,

in an act of unimaginable love.

When Catherine says

that we must know that we are not,

she is saying that we must know that we exist

only because God has loved us into existence,

and we must also know that

when we turn away from God

we begin to disappear back into nothingness.

To dwell in the house of self-knowledge

we must both acknowledge ourselves

as artifacts of divine love,

and understand how catastrophic it is for us

to turn away from that love

to a fruitless love of ourselves.

cannot come truly to know ourselves

without knowing God.

And what we must know

about ourselves and about God

is that God is, as he declares to Moses,

“I am who am”—the One who is—

and we, in contrast, are the ones who are not.

What Catherine means by this

is that it is God’s very nature to exist,

and that everything else in the universe

has been created by God from nothing.

So while God is the One who is,

we are beings who have been drawn by God

out of nothingness into existence,

in an act of unimaginable love.

When Catherine says

that we must know that we are not,

she is saying that we must know that we exist

only because God has loved us into existence,

and we must also know that

when we turn away from God

we begin to disappear back into nothingness.

To dwell in the house of self-knowledge

we must both acknowledge ourselves

as artifacts of divine love,

and understand how catastrophic it is for us

to turn away from that love

to a fruitless love of ourselves.

During Lent we should ponder

this double truth about ourselves,

the grandeur and misery of our condition.

We should hear Jesus’ words,

“if you do not repent,

you will all perish as they did!”

not as a threat of divine punishment,

but as an invitation to let grace turn us back

to the God who has loved us

out of nothingness into existence.

We should hear St. Paul’s words,

“whoever thinks he is standing secure

should take care not to fall,”

not as an exhortation to anxiety and fear

but as an invitation to us, who are not,

to plant our feet more firmly

on the solid rock of the One who is.

Our recognition of our own poverty

should make us only marvel more

at the richness of God’s grace

that has been bestowed upon us.

Our Lenten self-examination,

if it can pierce our self-deception,

should lead us to sincere sorrow

for our sins and failings,

but also to a deep gratitude to God

for our creation and redemption

and our hope of eternal glory.

We begin Lent as the fruitless fig tree,

having done little with the time bestowed on us,

but given by grace one more season to turn

from the sterile self-love that pulls us into nothingness

back to the embrace of the God who loves us.

And within that embrace we can become

like the thorn bush from which God spoke to Moses,

ablaze but not consumed by the fire of the One who is,

beacons that draw others into the embrace of God.

if it can pierce our self-deception,

should lead us to sincere sorrow

for our sins and failings,

but also to a deep gratitude to God

for our creation and redemption

and our hope of eternal glory.

We begin Lent as the fruitless fig tree,

having done little with the time bestowed on us,

but given by grace one more season to turn

from the sterile self-love that pulls us into nothingness

back to the embrace of the God who loves us.

And within that embrace we can become

like the thorn bush from which God spoke to Moses,

ablaze but not consumed by the fire of the One who is,

beacons that draw others into the embrace of God.

In this Lenten season,

may we come to know ourselves

as we come to know the One who is,

and may God have mercy on us all.

may we come to know ourselves

as we come to know the One who is,

and may God have mercy on us all.